BY THOMPSON REUTERS FOUNDATION

The sign is ubiquitous: six words that are painted on walls and homes across Uganda, like a national motto, from quiet banana groves to the frenetic capital Kampala.

“This plot is not for sale.”

The words are as much to inform the unwary as they are to deter the conmen, who sometimes collude with land officials to obtain fake titles.

The sign is meant to ward off “quack brokers”, said Vincent Kirabo, an ex-teacher turned businessman in Kampala. He is referring to people who sell land while the true owners are away, often using counterfeit titles.

“It has entered the language now,” he said. “People call it ‘buying air’.”

Ten years ago, Kirabo returned from studying in Britain to find some of his land had been sold using forged documents, and had passed through the hands of several innocent buyers. The court case to reclaim his property is still dragging on.

That is why he painted a “not for sale” sign on the perimeter wall of another piece of his land in Kampala. He also hired a guard to sleep there.

Nearby, Rachel Namaganda scrubs cooking pots outside her tin-roofed house. The magic words, with a phone number, are scrawled next to her door too.

Namaganda usually sells banana pancakes in town. But, during a recent crackdown on vendors, she went back to her village. While there, she heard that her Kampala house was up for sale.

“That’s why I wrote those words,” she said, nodding at the door. “If someone knows that you are not around, they can sell your property.”

RAMPANT FRAUD

Andrew Bashaija is the judge who heads the land division at the High Court. He told the Thomson Reuters Foundation that fraud is “rampant”.

“Most of the cases we handle here – I can say 75 percent-plus – are fraud-related cases,” he said. “We have instances where officers in the land registry, unfortunately, are involved in the same fraud.”

He gave examples where titles were transferred rapidly between several people, passing land on to third parties and covering for the initial forgery.

“Sometimes there are two, three, four minutes in between those successive transfers,” said Bashaija. “It raises red flags.”

Other legal experts also suspect collusion between conmen and officials.

“When you look at the forged titles, sometimes it even has the seal of the land office,” said George Musisi, a lawyer at the Foundation for Human Rights Initiative, a charity that offers legal aid services.

The authorities have taken some steps. The commissioner of land registration, who is suspended, is facing prosecution over claims that she registered land to the wrong owners in 2011.

And a public enquiry, which has spent a year probing land policies and practices, has heard numerous reports of fraud.

Dennis Obbo, a spokesman for the land ministry, said fake titles “come from outside the system,”, although he conceded that on occasion agents would “collude with individuals within [the land offices]”.

He said a computerized land registry had dramatically reduced fraud: 752,000 land titles have been entered into the system, with the process scheduled to complete in a year.

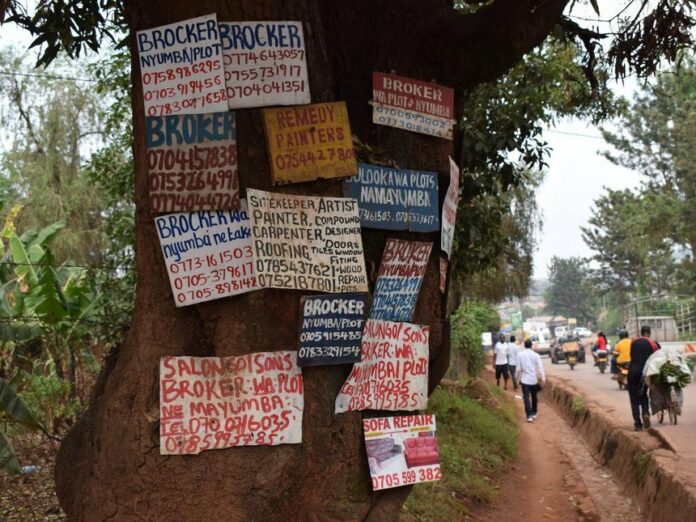

He said the government also plans to register land brokers, though no law is in place for that.

“Any person can become a broker in Uganda … They handle documents of clients that are worth billions and billions of shillings, yet we don’t know them, they are not registered.”

BOX OF TRICKS

Fake land titles are one of the many tricks conmen use to dupe potential buyers, said Geoffrey Tumusiime, a broker. In some cases, conmen masquerade as elderly family members or pretend to be local officials to witness the transaction.

“He brings an old man and says this is my father. He makes an agreement, and when you come in you find this person is not the owner.”

Disputes also arise when the landowner dies and family members squabble over the inheritance. Michael Wanyeera, a local council chairman in a poor part of Kampala, dealt with one such incident.

“One side said they didn’t want the land to be sold, and the other one said that we want to sell it,” he said.

Eventually some family members sold the land behind the others’ backs.

And going to court, as Vincent Kirabo found, is a slow and costly process. In 2017, a judicial committee found there were 22,413 pending land cases, of which 6,669 had been in the court system for at least two years.

As pressure on land increases, especially in Kampala and surrounding districts, more Ugandans are painting “this plot is not for sale” on their property to protect it.

“This is the problem these days,” said Wanyeera. “One plot has two land titles, three land titles, and you fail to know which is the real one.”

“Those signposts that are written, they are written in fear.”