The following feature was first published in Seeds of Gold.

Some 80km from Kisumu town off the highway to Bondo in Kondigo village, Seme, sits Magana Farm.

It takes about an hour-and-a-half from Kisumu to reach the village. A kilometre-long murram road leads to the farm owned by Patrick Magana.

“I keep everything and grow anything,” says the farmer of his three-acre farm.

Magana can be aptly described as a jack of all trades as he keeps dairy cows and goats, indigenous chickens, bees and grows tree seedlings, maize and mangoes.

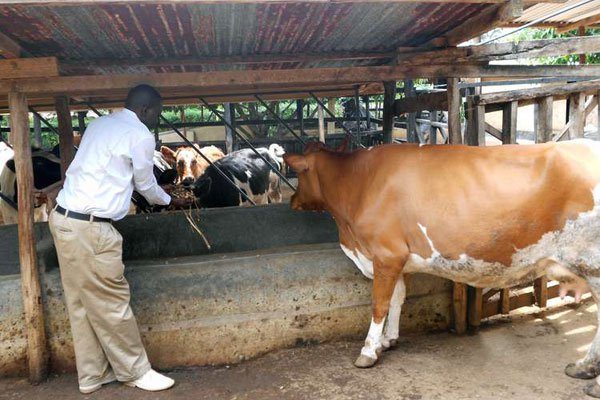

In the dairy shed, his Friesian and Ayrshire cows chew diligently. Magana, 56, had just served them silage that he makes on the farm.

The cows produce 28 litres of milk each a day. “We milk them twice. Currently, we are milking four that are at different stages of lactation,” says Magana. The cows are mainly fed on silage and dairy concentrates.

The farmer has been keeping cows for the last 20 years — dairy farming being his premier venture, and sells the milk making up to Sh150,000 a month.

“I sell to schools and restaurants at Sh70 a litre. On average, my milk man distributes five litres each to three local schools. I have a restaurant in Seme that picks 11 litres daily. Residents also buy the milk at Sh60 a litre,” says the father of five children.

The dairy cows are bringing in handsome profits for the farmer, thus, one would have expected he concentrates on the venture to reap maximum benefits.

But mono-farming is not the farmer’s staple. “I practice mixed farming because it helps me earn a decent living from the soil. If I had concentrated on cows only, what happens when the price of milk drops?”

At a separate shed, 30 dairy goats of the German Alpine breed, which he acquired from Nyeri through their dairy goat association, bleat loudly.

The Dairy Goats Association of Kenya (DGAK) in 2013 gave the farmer four does and a buck.

“I was supposed to hand them the four kids after reproduction and remain with the parent stock. The number has grown since then,” says Magana.

MIXED BAG

In the goat shed, each cube hosts three does. The bucks are kept separately.

He feeds them on fodder shrubs like calliandra, tricandria, lucerne, desmodium, Boma Rhodes, silage and salt lick.

He milks four goats that are at different lactation periods, with each offering him three litres of milk, which he sells at Sh100 earning at least Sh20,000 a month.

“Demand for goats is so high that we cannot satisfy the market. Last month, a client from Busia wanted 400 goats. I could only sell 10 at Sh15,000 each, the rest were bought from Central Kenya,” recounts Magana, who sells the animals from seven to 12 months.

The goats’ shed is raised to free the animals from cold and dampness since they are prone to pneumonia.

The farmer sprays and deworms the animals twice a month. He has three employees, who ensure the cow and goat sheds are clean and the animals are well-fed.

He carries out routine pest and disease control after every fortnight. He often uses the pour-on chemicals, which are applied on the animal’s body for the control of ecto-parasites like ticks and diseases they transmit.

The method helps to keep off tsetse flies and other insects from attacking the animals, he says, noting that spraying is only good at controlling ticks. The only disadvantage of the pour-on method is that it is expensive. There is also danger of pest-resistance if the farmer doesn’t use the right concentration.

“During the rainy season, I plant maize for animal consumption. Once the crop has started to flower, I cut and chop it with the chaff-cutter and make silage that lasts for three months,” says the farmer, who started dairy farming with two Zebus in 1991, which cost him Sh9,000 each. He crossed them with Friesian and Ayrshire, ending up with his current stock.

He has constructed a 16 cubic metres biogas digester from where he gets his fuel for domestic and farm use.

Patrick Magana in his farm in Kisumu County where he grows fodder, keeps goats, bees and cows.

“With nine animals, we are making more gas than we need on the farm. If we could know how to pack, we would sell it,” says Magana, who uses the slurry from the farm to grow crops.

The farmer keeps 100 chickens of the Rainbow breed, which is a dual-purpose bird. Last month, he sold 50 birds to three restaurants in Kisumu at Sh500 each. He sells the eggs at Sh15 each.

Away from livestock, mango trees and various tree seedlings sway gently to the wind. At the tree nursery, he grows eucalyptus, cypress, acacia, calliandra, gravelia and various indigenous seedlings.

The seeds go from Sh10 to Sh15 depending on the variety, enabling him to make more than Sh100,000 in a good month.

The farmer has over 200 grafted mangoes in his orchard, which also hosts 20 beehives.

“I started by growing mangoes then I realised I needed the bees to pollinate them. That is when I went into bee farming. I grow Apple mango, Tommy Atkins, Ngowe and Kent varieties.”

“I sell the mangoes mainly to a supermarket in Kisumu and traders in local markets. Last season, I made Sh40,000 from the crop but prices were lower due to market forces,” adds Magana, who depends entirely on the farm to feed his family.

START SLOWLY

He has also educated all his children with proceeds from farming, the last-born who is in university.

A single beehive can approximately produce 10kg of honey after three months. The farmer sells a kilo for Sh700 and harvests between 70 to 80kg a season.

“I am up by 5am to ensure the cows and goats are milked and the milk is delivered to buyers. I also have to check on the goats, poultry, bees, mangoes and tree seedlings,” says Magana, who has been a farmer for all his adult life and has attended various trainings.

Of all his ventures, he loves the dairy cows most because it is through the sale of milk that he has been able to expand to dairy goats, poultry, bee keeping and fruit farming.

“Mixed farming is a blessing. I get milk from the cows and goats and then use their waste to produce biogas. The biogas has the slurry which I use to grow crops, fodder, tree seedlings and mangoes. The bees collect nectar from the mangoes, thus, pollinate them. The farm is integrated in a way that enables me to get income all-year round.”

However, mixed farming method comes with its own challenges. “When starting, you should be ready to spend heavily on livestock and crop experts as you learn so that later, you can stop relying on them for some things.

However, to be a successful mixed farmer, do not start by growing many crops or keeping several kinds of animals. “If you do this you risk failure. Start with one project and introduce others as you gain confidence,” he says.

More income for Magana comes from trainings that he offers farmers and agriculture students. He charges Sh200 per farmer and Sh3,000 for a class of students.

David Mbakaya, an agronomist at Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation, says mixed farming is the way to go if farmers are to make more money and fight new challenges like climate change.

“The organic manure like slurry helps improve soil fertility. With biogas production, we reduce the cutting of trees as a source of fuel,” says Mbakaya, however, noting that the method of farming is capital intensive as one deals with various challenges that include diseases at ago.

This, however, can be mitigated through training so that one does not rely on hiring crop and animal experts all the time.

A farmer requires at least two acres to practice intensive mixed farming. However, it all depends on what he wants to keep or grow, he adds.