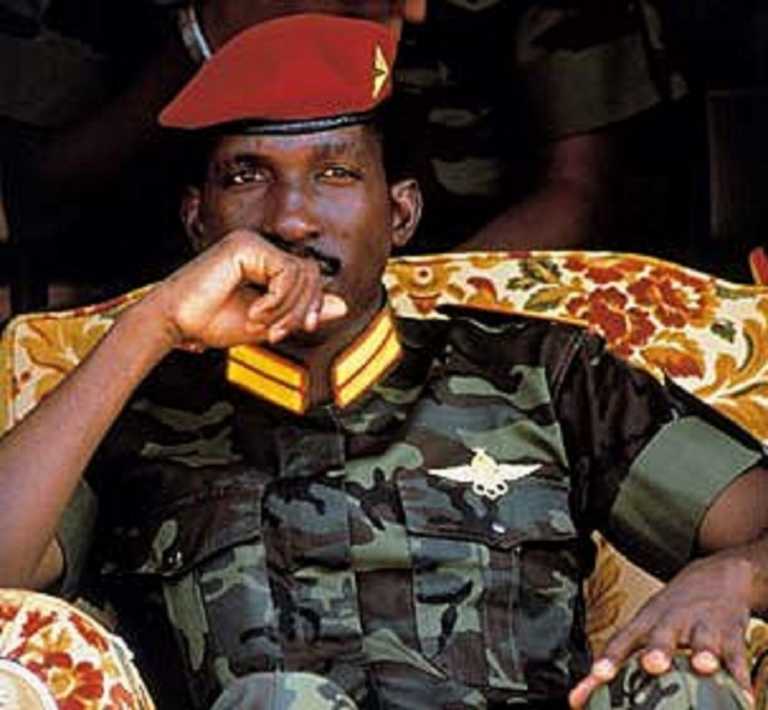

Thomas Sankara: Africa’s Che Guevara

Thomas Sankara was Burkina Faso’s president from August 1983 until his assassination on October 15, 1987. Perhaps, more than any other African president in living memory, Thomas Sankara, in four years, transformed Burkina Faso from a poor country, dependent on aid, to an economically independent and socially progressive nation.

Thomas Sankara began by purging the deeply entrenched bureaucratic and institutional corruption in Burkina Faso.

He slashed the salaries of ministers and sold off the fleet of exotic cars in the president’s convoy, opting instead for the cheapest brand of car available in Burkina Faso, Renault 5. His salary was $450 per month and he refused to use the air conditioning units in his office, saying that he felt guilty doing so, since very few of his country people could afford it.

Thomas Sankara would not let his portrait be hung in offices and government institutions in Burkina Faso, because every Burkinabe is a Thomas Sankara, he declared. Sankara changed the name of the country from the colonially imposed Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, which means land of upright men.

Thomas Sankara’s achievements are numerous and can only be summarized briefly; within the first year of his leadership, Sankara embarked on an unprecedented mass vaccination program that saw 2.5 million Burkinabe children vaccinated. From an alarming 280 deaths for every 1,000 births, infant mortality was immediately slashed to below 145 deaths per 1,000 live births. Sankara preached self-reliance, he banned the importation of several items into Burkina Faso, and encouraged the growth of the local industry. It was not long before Burkinabes were wearing 100% cotton sourced, woven and tailored in Burkina Faso. From being a net importer of food, Thomas Sankara began to aggressively promote agriculture in Burkina Faso, telling his country people to quit eating imported rice and grain from Europe, said, “let us consume what we ourselves control,” he emphasized.

In less than 4 years, Burkina Faso became self-sufficient in foods production through the redistribution of lands from the hands of corrupt chiefs and land owners to local farmers, and through massive irrigation and fertilizer distribution programs. Thomas Sankara utilized various policies and government assistance to encourage Burkinabes to get education. In less than two years as a president, school attendance jumped from about 10% to a little below 25%, thus overturning the 90% illiteracy rate he met upon assumption of office.

Living way ahead of his time, within 12 months of his leadership, Sankara vigorously pursued a reforestation program that saw over 10 million trees planted around the country in order to push back the encroachment of the Sahara Desert. Uncommon at the time he lived, Sankara stressed women empowerment and campaigned for the dignity of women in a traditional patriarchal society. He also employed women in several government positions and declared a day of solidarity with housewives by mandating their husbands to take on their roles for 24 hours.

A personal fitness enthusiast, Sankara encouraged Burkinabes to be fitted and was regularly seen jogging unaccompanied on the streets of Ouagadougou; his waistline remained the same throughout his tenure as president.

In 1987, during a meeting of African leaders under the auspices of the Organization of African Unity, Thomas Sankara tried to convince his peers to turn their backs on the debt owed western nations. According to him, “debt is a cleverly managed reconquest of Africa. It is a reconquest that turns each one of us into a financial slave.” He would not request for, nor accept aid from the west, noting that “…welfare and aid policies have only ended up disorganizing us, subjugating us, and robbing us of a sense of responsibility for our own economic, political, and cultural affairs. We chose to risk new paths to achieve greater well-being.”

Thomas Sankara was a pan-Africanist who spoke out against apartheid, telling French President Jacques Chirac, during his visit to Burkina Faso, that it was wrong for him to support the apartheid government and that he must be ready to bear the consequences of his actions. Sankara’s policies and his unapologetic anti-imperialist stand made him an enemy of France, Burkina Faso’s former colonial master. He spoke truth to power fearlessly and paid with his life. Upon his assassination, his most valuable possessions were a car, a refrigerator, three guitars, motorcycles, a broken down freezer and about $400 in cash.

Few young Africans have ever heard of Thomas Sankara. In reality, it is not the assassination of Thomas Sankara that has dealt a lethal blowed to Africa and Africans; it is the assassination of his memory, as manifested in the indifference to his legacy, in the lack of constant reference to his ideals and ideas by Africans, by those who know and those who should know. Among physical and mental dirt and debris lie Africa’s heroes while the younger generations search in vain for role models from among their kind. Africans have therefore, internalized self-abhorrence and the convictions of innate incapability to bring about transformation. Transformation must runs contrary to the African’s DNA, many Africans subconsciously believe.

Africans are not given to celebrating their own heroes, but this must change. It is a colonial legacy that was instituted to establish the inferiority of the colonized and justify colonialism. It was a strategic policy that ensured that Africans celebrated the heroes of their colonial masters, but not that of Africa. Fifty years and counting after colonialism ended, Africa’s curriculum must now be redrafted to reflect the numerous achievements of Africans.

The present generation of Africans is thirsty, searching for where to draw the moral, intellectual and spiritual courage to effect change. The waters to quench the thirst, as other continents have already established, lies fundamentally in history – in Africa’s forbears, men, women and children who experienced much of what most Africans currently experience, but who chose to toe a different path. The media, entertainment industry, civil society groups, writers, institutions and organizations must begin to search out and include African role models, case studies and examples in their contents.

For Africans, the strength desperately needed for the transformation of the continent cannot be drawn from World Bank and IMF policies, from aid and assistance obtained from China, India, the United States or Europe. The strength to transform Africa lies in the foundations laid by uncommon heroes like Thomas Sankara; a man who showed Africa and the world that with a single minded pursuit of purpose, the worst can be made the best, and in record time too.