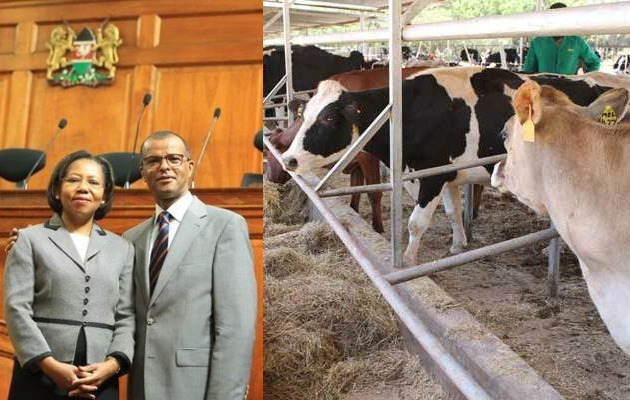

Best dairy farms in Kenya: Moiben Dairies Limited belongs to former Director of Public Prosecutions Philip Murgor and his wife Agnes, who is a judge of the Court of Appeal.

Theirs is a story of ambition, risk-taking and unparalleled optimism to establish one of the best dairy farms in Kenya. Having witnessed the challenges of grain farming, the Murgors ventured into dairy farming in an otherwise difficult atmosphere. And on this they have staked all — including the future.

Revealed: The late Daniel Moi’s final moments before death

“There is no money in grain farming,” says Philip. “There is a description of a mad person as one who repeats the same hopeless activity, but expects different results. We decided to try something different.”

The Murgors insist Kalenjins don’t count their cows. So it was difficult to get Philip to answer that question. However, he finally said he had 390 of them on the 650-acre farm. And he knows all of them by number.

The two lawyers have another side which probably few Kenyans know: a strong passion and commitment to agriculture.

They may be comfortable on the city elite circuit mingling with the rich and powerful and talking matters law and politics as most lawyers are wont to.

But at the farm, they speak like veterinarians. They seamlessly complete each other’s sentences on diverse farming topics, using expressions like milkers, silage, baling, Boma Rhodes and elmba.

Kings Prism Tower: The modern office space nobody wants to rent

They collect about 500 litres of milk a day. By selling the milk at Sh35 per litre, they fetch an average of Sh17,500 daily and Sh450,000 per month. But that is not their target.

“This is a breeding farm. But when cows produce calves, you get milk. The cash we get from milk is ploughed back to pay salaries for our workers and buy feeds for the animals,” he says of one of the best dairy farms in Kenya.

TOP BREEDERS

Philip insists that “our future is here”. And says they want to be the top breeders of high pedigree cows in the country.

“We aim to build a herd of 1,000 cows and put out at least 100 heifers a year at Sh300,000 each,” he says, leading us to a feeding stall with 85 milk cows Agnes is feeding.

The dry cows and calves are in different paddocks while the cross-breeds are roaming the expansive farm for pasture.

“We are breeders of Holstein and Jersey pedigree cattle though we have not attained the critical mass that will enable us offer significant numbers every year to the market,” says Agnes.

Their long-term strategy is to grow their Holstein herd and buy more Jerseys to improve butterfat content in milk production.

Philip says he inherited the farm from his mother Christine Chebor, who was a prominent wheat farmer. In the early 1970s, the land was owned by the Emslie family, who were Afrikaan settlers.

Because Moiben is a marginal area compared to other parts of Uasin Gishu County, the Murgors attract a lot of attention as the area is not known for successful dairy farming.

They faced two major challenges when they started. First was the acquisition of stock. The other, and the more expensive, was development of infrastructure that is now complete and is capable of housing more than 200 head of pedigree cattle, and about 150 hybrid animals.

“We have completed the developmental stage which was the most challenging. We are now raring to go. We should be selling heifers later in the year,” says Philip.

So what is the trick in running one of the best dairy farms in Kenya?

Commitment, acquisition of appropriate stock, professional management, proper infrastructure, proper insemination, a strict feeding regime, innovation, time and the courage to dream.

The Murgors split their time between Nairobi and the farm. They have employed a livestock, agriculture and machinery manager to oversee activities at the farm.

“Despite the very busy professional lives both Agnes and I lead in Nairobi, we visit the farm almost every weekend to direct the critical activities,” he says. “When we eventually retire, we expect it will be to a thriving dairy cattle breeding enterprise.”

And this does not come easy, says Agnes, who gives us a glimpse into the life of a judge.

“We work throughout our lives. After hearing cases we have to carry the files home and burn the midnight oil writing judgments. We even work through the weekends,” she says, leading us to a section of the farm where she is practising horticulture to supplement the livestock project.

Agnes has started cultivating cabbages and onions for the local market using drip irrigation. She hopes to harvest three times a year.

The judge bursts out laughing as she explains her first failed attempt at vegetable farming.

“I cultivated onions here but I harvested very tiny ones due to bad seeds. I am determined to get it right with cabbages,” she says.

Best dairy farms in Kenya: PROFESSIONALLY-RUN BUSINESS

But why would a well-paid judge soil her hands in farming?

She says judges are not highly paid as many people think.

“The desire is to use the resources we have. And as I judge, I must do things that ordinary people do. Life is not about doing just one thing,” she says, adding that she enjoys farming.

The business is run under the umbrella of Moiben Dairies Limited in which the two are shareholders.

“We decided to avoid the kienyeji approach and turned our dream into a professionally-run business to protect it from the management challenges that characterise many family ventures,” says the judge.

The Murgors bought over 50 cows and heifers from Delamere estates in 2011, when the Naivasha-based firm wound up its dairy operations. Delamere developed its Friesian/Holstein breeds from the 1920s. Philip says they also bought stock from Uasin Gishu breeder JE Kruger and government owned Agricultural Development Corporation. This, he says, will make them among Kenya’s leading Holstein breeders. This is the best breed for dairy farming.

To cut cost, the Murgors buy used machinery and repair them in their workshop.

“We are scrap metal people. All my farm machinery is second-hand. I am trying to keep the project as loan free as possible,” says Philip.

That is how he bought the graders, hay mixers, coolers, milk machines, water pumps and tractors, among others.

Using the cheapest materials possible, the Murgors have also built feeding stalls, a modern milking parlour with cooler, spray race, and calf barns.

All milking animals are maintained in enclosed feeding stalls, while the dry cows and heifers are maintained in semi-zero grazing paddocks. The cross breeds graze in the farm.

To address challenges that come with breeding, they have a resident inseminator.

“Somebody once sold us dead semen. We decided to store our animals’ semen here and employed a resident inseminator to monitor the animals closely.”

The major challenge is water and animal feed. The milk cows are fed twice a day. The Murgors have dug several water pans and a dam in the farm from which water is drawn for the cows and for irrigation.

The strategy is to ensure that much of the animal feed comes from the farm.

Philip says apart from building up the numbers, creating feed stockpiles is a major, but not insurmountable, challenge. Ideally, a dairy farmer should stock up for at least two years to cater for the possibility of failed rains and drought.

“We achieve this by ensiling our entire maize crop, baling tonnes of Rhodes hay, wheat and barley stray. We also grow wheat, sunflower and barley for feed,” says Philip.

At least 150 acres are under improved pasture, comprising mainly elmba, Boma Rhodes and Sudan grass. Another 150 acres are used to grow maize for silage as wells as sunflower, barley and oats.

“We will be most comfortable if we have a more stable water supply. That is our headache right now,” says the former DPP.

HOW I SEE IT: WHAT FARMERS NEED ARE SUBSIDIES

The Murgors are happy that their three children have taken interest in what happens at the Moiben Farm despite being away in school most of the time.

“We are sure that one of them will later assume some responsibility on the farm,” says Philip.

Their first born, Carime, is a master of law student at Manchester University, UK, while Robert is doing ‘A’ levels. Celeste is at Consolata School.

Philip says the project has attracted attention from county officials and even foreign visitors.

He says most farmers failed in the 1980s and ‘90s due to lack of affordable credit and a compensation scheme that would cushion them against crop failure.

“ As I grew up I watched farmer after farmer fold up under the weight of debts. The most exposed were those engaged in grain farming,” he told Seeds of Gold.

The lawyer says farmers need subsidies and soft development loans.

“Otherwise Kenya will remain a net importer of agricultural commodities that could very easily be produced here and at a much lower cost than what it takes to import to cover shortfalls.”

Interested, need to pay a visit.

Are visits to the farm allowed?