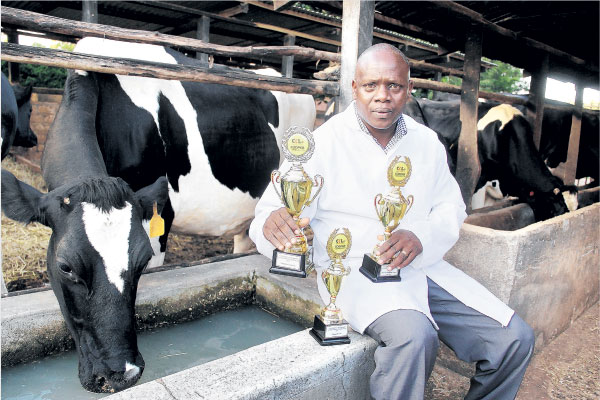

Dressed in a white coat, he is standing between wooden stands inside a cow shed. The structure is home to black and white-stripped Friesian cows on a section of his 50-acre parcel at Kapseret, west of Eldoret Town.

The cows are silently chewing on bales of what looks like dried grass in groups of four.

“To keep my cows happy, I give (them) all my attention from feeds to exercise,” Willy Kirwa, the proud owner of these pedigree cows informs us.

He has grouped the animals into high yielders, medium, drying and those that are steaming up. And there is a reason for this.

“Every cow requires different portions of nutrients. For example, when the cows are drying they need less proteins to prevent complications.”

And they are extraordinary, these giants of animals. They are pure breeds with huge udders. They produce a lot of milk and lactate for long.

But they were not always so. The cows are products of breeding that has seen Kirwa’s stock become better every year.

“Generally, when one raises a cow’s pedigree, its milk production improves. For instance, the off-spring produces five litres more than the mother. This goes on until you get a pure breed.”

Kirwa went into breeding after a field trip to Israel in 2008. He discovered that despite being a literal desert, the Middle East country was overflowing with milk.

“I set out to learn how to manage cows because I wanted to venture into it large-scale,” says the man, who dropped out of school in Form Two, and had been growing maize and wheat for 15 years with minimal returns.

TOP OF THE CHARTS

At first, he paid a visit to two farms in Kenya but he was dissatisfied. So he flew out to Israel where he learnt how to produce better breeds.

The flight marked the beginning of his journey to the top of the charts in dairy farming. From his three cows, which were on the foundation stage 10 years ago, he has attained 68 pure Friesian cows.

He uses sexed semen, which he says guarantees a heifer.

“With a female calf, you can double your herd fast and sell them to farmers who want to rear the cows,” the 45-year-old farmer says.

He serves the heifers once they reach 15-18 months and weigh 350kg. While a good bull can deliver a better offspring, Kirwa says, many farmers make the mistake of serving cows with the same bull over time.

“This means it could take as long as 15 years to get a pure breed. When one serves one bull all the time, the chances are that the same genes are passed from one generation to the other, including diseases.”

“When I want to improve the breed of a heifer, which produces 10 litres daily, I look for the bull whose mother produces 20 litres.”

Although ordinary insemination costs as low as Sh1,000 compared to Sh7,000 for sexed semen, the father of five says, one is not guaranteed of a heifer.

“It is like trial and error because you might need several attempts to get a desired breed,” says the farmer who sources his semen from some of the top breeding firms in the world.

From 30 lactating cows, he gets more than 450 litres of milk every day, which he sells to schools, hotels and a milk processor in Eldoret Town. Since the milk costs Sh40 a litre on average, the astute dairy keeper earns Sh18,000 a day.

Besides the milk, Kirwa makes a tidy sum selling pedigree heifers, whose demand, he says, crosses the Kenyan border to Tanzania, Uganda and Rwanda.

“I usually sell on average 10 heifers to farmers in a year because there is insatiable thirst for the cows,” he says. Each cow can fetch up to Sh200,000, he says.

These handsome rewards are not the sole work of breeding, though. Kirwa observes a strict feeding and health regime that makes his Willen Farm the envy of many.

Initially, he used to graze his cows in the open field, but this was giving him very little milk — as low as three litres per cow.

A trip to the dry Ukambani with fellow members of Eldoret Farmers Association exposed him to healthier cows raised under zero grazing.

He adopted the system even though land for him was not a problem.

IMPROVE THEIR PASTURE

“We learnt that when cows don’t move a lot and eat dry matter, they produce a lot of milk because they drink a lot of water,” says the farmer, who has built a spray race to battle the dreaded East Coast Fever and slash costs.

“I spent Sh300,000 to construct it, but I now spend only 12,000 per month instead of the Sh50,000 I used to spend. Cows also produce less milk when they jump and drown in dips.”

Friesians are heavy feeders. To cushion himself from high cost of animal feeds, Kirwa grows boma Rhodes and lucerne that are rich in protein.

He also top-dresses the field covered by Kikuyu grass with CAN fertiliser to nourish it. “For every acre, I apply 100kg of the fertiliser per year. Not many farmers know that this can improve their pasture many times over.”

It is in this lush field that Kirwa allows his cows to browse for two to three hours daily. He also plans to put one-and-a-half acres under rye — a grass grown in many parts of the world as a grain, a cover and forage crop. To further enrich his animals’ feeds, Kirwa grows maize from which he makes silage.

“This is mixed with grass, crushed and covered tightly with polythene. After a month, it is ready to be consumed. This is highly nutritious. It also ensures a constant supply of food supply, even during drought.”

By making his own dairy meal for the lactating cows, he saves Sh1,500 per 70kg of the high-yielding commercial dairy meal, which goes for Sh3,000.

And he feeds them according to production — cows that produce less than 15 litres should be given 2kg of dairy meal, 4kg for cows that give 15 litres and above and 5kg for those that produce 25 litres and above.

“Give a cow according to what it is giving you to avoid losses,” he advises.

Apart from the high cost of feeds, other challenges the dairy farmer grapples with are diseases like mastitis. He regularly monitors changes in milk colour and blood clots using a strip cup.

So why did he opt for Friesians yet their milk has low fat content and they eat to finish? “I looked at the market and saw most Kenyan dairy processors buy quantity. It makes economic sense to rear cows that produce the highest amount of milk,” he says.

Willen Farm is managed by Edwin Too, 28, a holder of a Veterinary degree from Egerton University.

Adjacent to his pen, Kirwa has built a biogas plant, which makes use of the waste from the cows. The slurry that is pumped from the plant is recycled.

The dark matter rich in urea finds its way into his one-acre orchard.

On a small farm nearby, there are cabbages, managu, sukuma wiki, beetroots and capsicum — produce he sells to hotels in Eldoret.

TRAINING FACILITIES

And Willen Farm has attracted a lot of attention and aroused a lot of interest.

In July, Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries Cabinet Secretary Felix Koskei came visiting.

Kirwa has also won several awards, including one for Best Cross Breed Cow during the Chepkoilel Agri-Business Expo in 2011 and the Best Friesian Cow at the Eldoret 2014 ASK show.

“After a dairy tour to The Netherlands, I found out that there are training facilities so I decided to construct one,” says Kirwa.

The farmer hosts up to 100 farmers monthly on his farm — another income generating venture for him.

I would like to be sponsored to pay a visit in one of the farm to improve my daily farming.