Hezron Ondigo Onyango was 14 years old when he walked into his father’s house in Eko village, Migori County and dragged him and his three elder brothers to the chief’s office. He demanded his share of his father’s land.

“My share was worth Sh162,000. Demanding it was my only way to get out of poverty,” says Mr Onyango, 35.

In his village, it was unheard of for a child to make such a demand. “My father had inherited six acres from our grandfather, but I was ready to dispose them to ensure I had a successful future,” he adds.

As the news spread, Mr Onyango was nicknamed the ‘Prodigal Son’. “My friends began avoiding me because they were told that I was bad company.”

His out of the ordinary decision was informed by a series of misfortunes in his early life. He had already watched his elder sisters get married at the age of 12 to escape the jaws of poverty gripping their family. His eldest brother was an alcoholic while the second born, John Modani, had died of illicit brews.

“At times I felt like we were bewitched. My father was so poor. He never contributed anything in the village and nobody would lend him cash because he never paid back. Villagers called him Arimuya, which means moneyless,” he told says.

In his early years, Mr Onyango believed that his father’s real name was in fact Arimuya. “I thought my father, Benson Onyango, was called Arimuya. He never protested to the name. He had internalised his poor state.”

However, he was determined to break free from the curse of poverty that had engulfed his family. “I wanted to curve out a better future for myself. I’d just finished my primary school education at Viyalo Primary School attaining 572 points out of 700 and I felt that to succeed, I needed schooling. I would use my inheritance to get it.”

He approached a primary school teacher asking to sell him half an acre of his inherited land.

“I took him to the chief’s office and we struck a deal. He would pay Sh70,000 for the plot of land. The money would be paid as fees,” says Mr Onyango who now holds a bachelor’s degree in education from Africa Nazarene University.

While he waited for his buyer to honour his part of the deal, Mr Onyango was employed as a groundnuts and samosa hawker in Migori town: “I couldn’t stay at home. There was no food. I preferred to trek to Migori town and work. My employer would pay me half the amount in cash and the other half with food.”

Although he had received admission at Rapogi High School, Mr Onyango joined Kakrao Day Secondary School, where his Sh70,000 could sustain him.

“I sat for my Kenya Certificate for Secondary Education in 1998 and managed a grade B- (minus). He applied and got admission offers for self sponsored study programmes from the University of Nairobi, Inoorero University and Multi Media University to pursue a degree in commerce, law and journalism. Although I never joined any of these institutions, the letters gave me hope that I was destined for success.”

In 1999, aged 19, he sold the other half of his land at Sh90,000 and enrolled for a teaching course at Thogoto Teachers Training College.

“I applied for the teaching course at a time when the government wasn’t hiring tutors. It looked like a gamble, but I foresaw opportunities that the course presented. I saw a future behind the chalk and board.”

In 2002, he graduated as the best student in the college. And in 2004, he got a teaching job at a private primary school in Nairobi. In the same year, he was named the best Social Studies teacher in Nairobi County by the Kenya National Examination Council after producing the highest scores.

“Time was ripe for me to make my mark,” he notes. “I turned to writing textbooks, which became both my biggest challenge and breakthrough in life.”

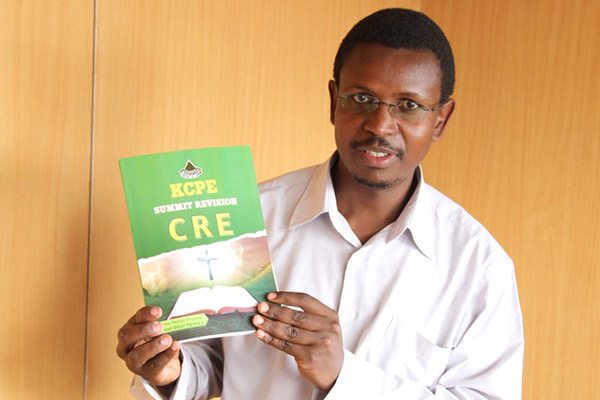

After publishing two books with Phoenix Publishers, he decided to go on his own. “I published two textbooks under my publishing firm, Hezzman Publishers.”

Five years down the line, his books have raked in Sh11 million after selling about 25,000 copies.

His books attract between Sh400 and Sh450. But marketing the publications has been his biggest challenge, he says. “It’s tough to sell your books in a field where you have a limited marketing network. But I have always believed in overcoming challenges,” he says.

“I have since established valuable networks by visiting schools across the country, and advertising in education journals and educational open days.”

The entrepreneur also conducts private tuition, a venture that brings him Sh60,000 per month on average.